by Janet Fang

Horses with what’s called Dun coloration sport a mostly pale coat with a few dark-colored markings, like a stripe down the back or a series of streaks on the legs. Most horses these days are non-dun, though Dun is thought to be the ancestral coloration.

Researchers have now identified the genetic mechanism behind these so-called “primitive markings,” and their findings, published in Nature Genetics this week, suggest that Dun was important for camouflage in wild horses. A similar mechanism may be responsible for the vivid black-and-white stripes of zebras.

The Dun coat color is characterized by pigment dilution that affects most of the body hair, leaving patterns of darker areas with undiluted pigmentation. The most common features are a dark dorsal stripe (pictured to the right) or zebra stripes on the legs (pictured below). Diluted pigmentation represents the wild-type state. Przewalski’s horses – the only remaining wild horses – are close relatives of the ancestor of domestic horses, and they’re all Dun colored. So are other wild members of the horse family: the kiang, onager, African wild ass, and the quagga, a now-extinct subspecies of the plains zebra. The majority of modern horses have lost the Dun pattern, showing more intense colors that are uniformly distributed instead.

Non-dun horses, the team found, carry one of two mutations on a gene called TBX3, which codes for the T-box 3 transcription factor. These mutations cause the gene to be expressed at lower levels in the skin of non-dun horses than in Dun horses, though it doesn’t affect the function of TBX3 in other tissues. In both mice and men, TBX3 controls several important processes that affect the development of teeth and genitals, for example.

“The region of the body where TBX3 is expressed may account for the stripe pattern, whereas the region of the hair where TBX3 is expressed may account for color intensity,” Stanford’s Kelly McGowan explains in a statement. In Dun horses, the TBX3 protein is expressed asymmetrically in the hair bulb, where it blocks pigment production: Hairs are pigmented on just one side of the hair shaft, causing the diluted, lighter appearance of a Dun horse’s coat. The individual hairs in dark areas are intensely pigmented the whole way around.

The team identified two variants of the gene (or alleles) called non-dun1 and non-dun2. The latter form is more recent. When they compared modern horse genomes to 43,000-year-old horse DNA, they found that the Dun and non-dun1 alleles were already present in ancient horses – and they predate domestication. The mutation was likely selected for by humans, and the more recent non-dun2 variant occurred after domestication. While Dun coloration provides camouflage for wild horses by making them less conspicuous, humans selected against camouflage in favor of more conspicuous colors.

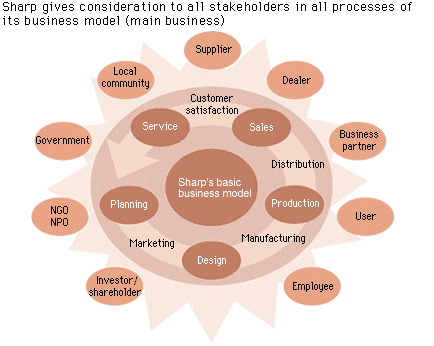

Examples of dark facial masks, dorsal stripes, shoulder crosses, and zebra-like leg stripes of Dun horses. Freyja Imsland and Páll Imsland

Image in the text: Freyja Imsland